By Indulata Mohanty | PUBLISHED: 20, Apr 2013, 15:26 pm IST | UPDATED: 08, Aug 2015, 14:47 pm IST

There was a banyan tree at the point where our village road touched the road that led to the town. It was not a very old one, but the branches were so well spread out that if one stood below it, it gave the feeling of standing below the ceiling of a big hall.

That was at one end of the village. In those days the village school was built at one end of the village, a little away from the dwelling houses. The Middle English School of the village was situated about thirty to forty feet from the banyan tree.

Vey near to the tree and by the side of the road, was the house of Padan kaka. Earlier he was staying inside the village, in Choudhury’ Saai’. His ancestral home became congested after its division among the brothers. He opted to come out and built a house here on a piece of land that he got as his share of the ancestral property.

The house was by the side of the road that led to the town. Not far from it, at a little distance from the road, a river flowed; a river for name sake, but actually it was a nulla. There was water in it throughout the year.

Around the house, in the open space there were a number of shady trees like mango, jamun and tamarind. It was the right place for settling down. Some other families had also their houses in this area for the same reason of congestion in the village. Gradually the area took the shape of a’saai’. But Padan Kaka’s house stood apart from others’.

The town was five or six miles from this point. Now, this distance is considered to be a trifling, but in our young days it was quite a bit. So, when Padan kaka pedalled his rickshaw to the town early in the morning and returned in the evening, we took this to be an achievement. Any one, who intended to go to the town by rickshaw, would invariably send a word to Padan kaka the previous evening. Guests usually ride to the village in Padan kaka’s rickshaw.

None of us, me and my friends had seen the town till then. Padan kaka’s son Pahali was my class mate. He was good in studies. School teachers considered him to be a good boy.

It was not that we were friendly to Pahali because he was a good student. As his father was going to the town every day, he was getting some new articles more often, new things like a pencil having an eraser at the other end, a fountain pen, beautiful top, glass balls or a kind of lozenge which had a cumin-seed at the core.

To us, these articles seemed to have come from another world! Although we were forbidden by our teacher to use a fountain pen lest our handwriting go bad, never the less we did use it clandestinely by the grace and magnanimity of Pahali. While all of us carry our books neatly wound in a piece of cloth called ‘bastani,’ Pahali was the only boy to use a proper school bag which he carried on his back. His both hands were free to walk in comfort.

For this reason, Pahali had a special standing amongst the friends. We used to go in a group to his house in the recess to a see a new item brought by his father. In fact we never went to his house. We waited under the shade of the banyan tree.

Padan kaka made a platform around the trunk of the banyan tree with clay. It was well compacted. Pahali’s mother, Ranga kaki made the platform smooth and tidy with a thin layer of diluted cow dung. We used to gather on that platform to see and play with Pahali’s new articles. At the end of the recess we used to run back to the School.

Modernization came to our village with electricity when we were in class Six.

First the streets were lighted up. With well lighted streets we no more waited eagerly for the bright half of the moon. We forgot to keep count of the bright or dark half of the moon.

A light was fixed at the point where our village road met the main road, near Padan kaka’s house. The front portion of the house as well as the platform around the trunk of the banyan tree was well lighted. That was enough to attract the elderly persons, who normally gather at the club house of the village for a round of cards or dice, to that platform under the banyan tree. As such, Ranga kaki used to clean the platform. Now that it was used as a place for recreation, she cleaned it daily, more meticulously than before.

We were promoted to class Seven. That was our last year in the School. Those who would pursue higher studies would either stay in the hostel of the High School in the town, or walk three miles to the High School at Mukundapur. One who would not be able do either, had to wind up his formal education.

We were not worried for the future. Our duty was to do our lessons well. It was up to the parents to decide where we study. Of course a tinge of fear was lurking at the back of our minds along with the thrill and joy of going to a new and unknown place.

At this time an amazing incident took place around the banyan tree which created much furore among the villagers; the children, the young, middle aged and the old, all alike.

That was the first Thursday of the month of ‘Margashir’. Ranga kaki woke up early, before the dawn, when darkness was still prevailing. She cleaned the area around her house with a broomstick and then sanctified it by sprinkling cow dung diluted with water. After taking bath she drew the feet of goddess Laskhmi, and the lotus flower with diluted rice paste.

After completing her routine chore at the house, she felt an urge of drawing designs on the platform around the banyan tree. There was a mild fog all around. Although the day had broken, visibility was low due to the fog. While on the job she could see something close to the trunk of the tree which she had not noticed before. Ranga kaki abandoned her work to see what it was. She could see a thing, brown in colour, which appeared to have popped up close to the tree trunk.

Her first reaction was that it was the hood of a cobra. She fell back a few steps. She then pulled a dangling root of the banyan tree to make noise and vibration. The thing did not move. Ranga kaki mustered enough courage to go near it. She took it under her hands. “Oh, Lord!” She cried out. She kept it back and ran to call her husband. “Look, is this not ‘shalagram’ stone? Has Lord Narayana come to us in place of goddess Laskhmi?”

The news spread in lightening speed. There was much din and bustle in the village. The villagers were astounded. Everyone of the village ran to see for himself, casting aside the job in hand. Even the women who were half way through the ‘pooja’ of goddess Laskhmi left Her waiting to see Lord Narayana under the banyan tree. The children still sleeping woke due to the commotion and ran lest they would be deprived of witnessing something special.

By the time the sun rose, there were lot of people around the banyan tree, not only from our village, but from the nearby villages also. They gathered a little away from the platform. They did not dare to touch it or set their feet on the platform as they had not bathed.

The priest of the temple of Lord Baladev and the Sanskrit pundit who lived in the Bramhin Village across the river were sent for. The gathering waited for them impatiently. On hearing the news both of them hurried to the spot. The people surrounding the platform gave them the way with due respect and waited with bated breath to hear what they say.

Both of them closely examined the piece of stone by lifting it into their hands with devotion. They discussed at length. They only know what they saw, discussed and contemplated; but ultimately declared to the public that it was not just a piece of stone, it was ‘Shivaling’, the Lord Shiva, the ‘Swayambhu’- the self incarnated.

Ranga kaki ran to her house, brought out a conch and blew it rhythmically for a long time. The other women present there joined her by sounding ‘hulahuli’. The men folk chanted ‘haribol’ in unison which filled the surrounding air.

What followed as a natural corollary was that with due pump and ceremony as was permitted by the pockets and with lot of devotion which was as intense as the sound of ‘mridanga’, ‘jhanja’ and ‘karatala’; the swayambhu- the self incarnated was duly enthroned near the trunk of the banyan tree as Lord ‘Vateswar’.

Thenceforth Padan kaka’s routine changed. Before pedalling his rickshaw to the town he collected a few flowers, bathed in the river and brought a jug of water from the river to bathe the lord. After bathing he decorated Him with flowers. He plucked a leaf from the banyan tree to use as a plate on which he put a piece of jaggery to offer to the Lord.

The elderly people modified their habit too. With the pack of cards and the dice board, they also brought musical instruments like mridanga, gini,and karatala with them. In the first session, they used to sit in front of the Lord in a semi circle to chant devotional songs in their incoherent voice to the odd and bizarre beating of the musical instruments.

In the second session they played card and dice. The women of the village came for the Lords ‘darshan’ as per their convenience. After the ‘darshan’ they threw some coins at the Lord’s feet. When all the people departed, Ranga kaki used to collect the coins and put them in an earthen pot specially made for the purpose. It had a slit through which a coin can go in but will not come out.

The pot filled up. Ranga kaki handed over the money to Padan kaka , “Buy a flag to put on the top of the tree, buy some fruits to replace the jaggery. The Lord should have the taste of the fruits also.”

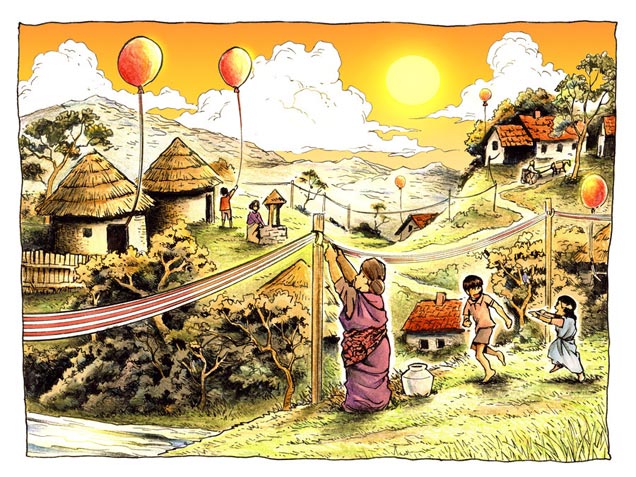

Vateswar was seated in our village; but his grace and blessings were not confined to our village only, they were well spread out. People of the neighbouring villages came to seek the Lords blessings for mitigation of problems they were having. They also came to express their gratitude if something good happened to them. Some came to seek divine interference in matters of deep concern.

In the mean time we passed out of the School. I went to the town and stayed in the School hostel. My friends, Pahali,Jugal,Sanatan, Chandranath and Sudhakar walked to Mukundapur daily as they enrolled themselves in the High School there.

I was coming to the village every vacation. Gradually I felt the oneness that was amongst us when we studied together was loosening up.

Each time I came to the village, I observed that the glory of Lord Vateswar was on the rise. In course of time I passed Matriculation Examination. Pahali also passed with good score. Others left their studies at different point of time to get engaged in the traditional profession of their families.

I got admitted to the college. Pahali preferred to go for C T training with the aim to be a teacher in the village M E School.

During my under graduate days I could not come to the village except in the summer vacation. After the degree examination, when I came to the village, I observed it had changed remarkably.

A small but beautiful temple was built for the Lord Vateswar with the money collected as offerings of the devotees and their voluntary labour. A big flag of nine hand-lengths atop the banyan tree proclaimed the Lord’s presence there. The flag could be seen from quite a distance. Needless to say, there was congregation both in the morning and the evening. On Mondays and other special days, like ‘Sankranti’, one had to wait for his turn to give his offerings.

Some old people were no more, new faces took their places in the evening ‘sankirtan’ and the round of games of card and dice which continued as before.

Pahali was a teacher in the village M E School. He got married. Things were moving in their own course and their own speed.

I joined the Government as a Deputy Collector after passing out the competitive examination for the Odisha Administrative Service. I got married. My parents left the village to stay with me at the place of my posting. So I lost direct contact with the village. Occasionally my uncle (Father’s brother) or his son Kishore visited us. I got news of the village from them. I could not make time to go there.

My parents left me. I was posted at different locations, sometimes at distant places. So I lost contact with the village. One day I received a letter from my uncle asking me to visit him urgently for a day or two.

The letter did not specify the urgency, so I reached my village with certain amount of apprehension. Time had cast its shadow on the people. The environment had undergone great changes. When I reached the boundary of my village, I asked to myself: Is this one my village?

The main road to the town was as it was. The village road which touched it was now a wide one. The banyan tree must have grown taller with time, but it was dwarfed by the temple of Lord Vateswar which was now a big one standing out majestically.

On the other side of the road and just opposite to the temple, the neglected pond which invariably dried up in the summer was now transformed into a beautiful one, full of water. Brick wall around the pond, flower plants of different varieties along its banks, and banana plantation below the banks enhanced its beauty. There were cement benches around the pond for people to sit and relax. My heart was filled with joy to see such a sight. I could not find Padan kaka’s house. A good looking pucca house stood in place where his mud walled, asbestos roofed house once was.

My apprehension was baseless. My uncle was hale and hearty. But I had not imagined in my wildest dream the reason for which he called me. He wanted division of the ancestral property. I objected, “Why, uncle can’t I and Kishore live as you and father did?”

Uncle’s reply was simple and to the point. He and his brother lived in the joint family. So there was no need to share the property. But I and Kishore do not meet each other for years! And, after retirement from the service, there was no possibility of my return to the village, as I have already built a house in Bhubaneswar.

I still protested. Kishore is my blood relation. I may come to the village on some occasions. Will he not allow me to stay here? Will he not give me food? Uncle made his mind clearer. Such a situation as pointed out by me would not arise, he said. The property was my grandfather’s. His two sons had equal right to it. In the absence of my father it was his duty to give me my share of that ancestral property; otherwise it would be construed that he did not do his duty. My father and grandfather would be unhappy at their heavenly abode. What explanation would he give when he joined them?

I had no reply. The papers for the division of property were made ready. I decided to pay a visit to Pahali. He embraced me. Instead of inviting me to his house, he led me to the pond. We sat on a bench in a secluded place.

Pahali had detail information regarding me. After exchanging pleasantries he said, “ I don’t know if you have the information: My mother’s strong desire and Lord Vateswar’s fame together upgraded the village Middle English School to a High School. The neglected pond that you saw in your childhood has taken this shape which you see now. The village road has been black topped.

“I heard all these in bits. Now I see them myself. Tell me, now, about you and your family.”

He told about himself. He passed B A and then B Ed. privately as he continued to a teacher in the village M E School. He then did his M A in Education, privately. He was now the Head Master of the Vateswar High School which was upgraded from the previous M E School and renamed.

I put my hand on his shoulder. His face brightened up and then he went into remorse. He said, “You know I married off my daughter. She is fine. I have a wish: To have a college in our village- in my life time. It is possible if the project is tied up with the name of Lord Vateswar. But my son has gone wayward. He is a scoundrel.”

I could not co-relate his son’s waywardness with the establishment of the college. I did not venture to probe as he looked dejected.

The division of the ancestral property was over. I handed over all the papers to Kishore and said, “I could not disobey uncle. Yet, I feel the property of our grandfather will not only be safe under your care, it will grow also. The entire responsibility is yours.”

I returned to Bhubaneswar. For many years I did not go to the village. My eldest son had gone to Birmingham for higher studies in medicine. When he returned after completing the studies, he was accompanied by a girl whom he had decided to marry.

The girl, Pamela, though of Birmingham, had her origin in India. Her great grandfather had migrated to England. In four generations the family became as coalesce of people of different caste, creed and religions. Even though they were no more pure Indians, yet they boast of their Indian origin. She had no idea of her original place in India. As she had lost hope of tracing her ancestors, she was eager to know those of Suprakash, my son.

So, after the marriage she was after me to go to the village. “Baba, please, let us go the village. Kaka told me that he still lives in that house which was built by great grandfather! I want to see that house and stay there for a while.”

I sent information to Kishore. Myself, my wife, son and daughter in law landed in our village. A kind of weird silence greeted me there.

Everyone was doing well. Everything was in order. I could feel people were better off than what I saw in my last visit. The all round development of the village was clearly visible. But no one was happy. No one was his usual self. A kind of fear gripped them all. A feeling that disaster may fall on the village lurked their minds.

We reached around lunch time. I took a nap after lunch. Pahali called on me. “Will you come with me if are not otherwise busy?”

I had no work on hand. Even if I had one, I would have gone with him leaving my job as I sensed urgency in his invitation.

He led me to the bench on the bank of the pond where we sat a few years back. I looked at him as he did not open the subject even after sitting there for considerable time. This is the first time I looked at his face since we left the house. I put my hand on his shoulder. “What is wrong with you, Pahali?”

He looked blank. With a dejected voice he said, “Nothing wrong with me. Only Lord Vateswar has left us, in His own style”

“Lord Vateswar left; in His own style!” I blurted out.

Instead of elaborating the statement he changed the topic. “Do you remember, we went for a picnic to the bank of the river Salia after the half yearly examination of class Six?”

Picnic was part of the curriculum in our school then. I failed to understand the significance of this particular one he was referring to. Yet I said, “Yes, I remember it well.”

“We went to the spot where Salia came down to the plain land from the hills. Innumerable small stones of different sizes and colours were scattered on the river bed.”

“Yes, I remember very clearly. We collected a few of them.” “I liked one among all those. It was slightly bigger than others and its colour remarkably different. I brought it home. Then something struck my mind. I kept it close to the trunk of the banyan tree, probably to show it to all of you in the recess next day.” Pahali said and then continued,

“Next morning, when I woke up, the piece of stone was already transformed to Lord Vateswar. I could not muster enough courage to speak out the truth. When I grew up I was afraid to hit at the belief of so many people. I consoled myself : What is the form of the Lord? The form of the Lord is in our belief. When so many people have reposed so much faith in the piece of stone that I picked up, it must be the manifestation of the Lord. This line of thinking generated faith in me also. I was relieved. My mother’s faith was total, cent per cent. She meticulously kept aside all the money donated by the devotees. She worshipped this money as Lakshmi. Each pie was spent for the Lord. My wife also followed suit, never deviated from that path.

But my son-, I don’t know what inauspicious time he was born in, started business by selling the Lord’s name. He collected money in the name of the Lord. He prevailed upon the political aspirants that the Lord’s grace could win them elections; he convinced the parents that the Lord’s blessings would find them a good match for their daughter, government employees would be transferred to posts and places of their choice and many such things! He committed such heinous acts in the name of the Lord. He was encouraged by his self centred wife. Her argument was that without money how would they live well, eat well and have a good house to live in?

I tried my best to mould them, bring them to the road of righteousness; but they paid no heed to my advice. As days passed, this became unbearable to me. I could not tolerate such unethical acts in the name of the God. Without any one’s knowledge, I put back the stone from where I had picked it up.

The whole village was in turmoil. The elderly people opined : Bad days are coming. The Lord had come of His own accord. The whole village prospered. Perhaps He saw such acts of ours which are forbidden by the scriptures. So He left as per His own will. Who will save the village now?

This is now in the mind of each one in the village. There is fear inside. But my scoundrel son was after my mother. He thought, she was responsible for this. She had hidden the Lord somewhere

My mother’s devotion was pure and total. After the Lord disappeared she hardly took any food. She told her grandson: how can I hide the Lord who is the master of the universe? He came on His own; now He decided to go back. Probably He did not like this place any more. My son did not believe in what my mother believed firmly.” I wanted to intervene, before I could, Pahali said, “Ma did not survive after the Lord left. Ma’s demise and the fear psychosis of the village folk have put me in a fix; a sense of guilt has crept in to me. I am not able to tell the truth to anyone. Tell me Jagat, have I gone wrong?”I was speechless. I went closer, put my hand on his shoulder, to assure him that he did not.

# Original Odia Story: Indulata Mohanty

# English Translation: Rabinarayan Patnaik

by : Priti Prakash

This week has thrown up a firestorm of global developments. Let's dive into the top 5 internati...