By FnF Desk | PUBLISHED: 28, Oct 2012, 0:10 am IST | UPDATED: 28, Oct 2012, 11:19 am IST

There is nothing Chen Maa cannot tell you about bicycles. For 40 years he repaired them from dawn until dusk in a battered lean-to he built himself a stone's throw from the Forbidden City. Then, as the Chinese capital was made ready for the 2008 Olympics, a wrecking ball swung in a single arc and wiped away his workshop.

"Everyone knew me," he says proudly. "They called me the King of the Spokes." Chen Maa holds up his fingers for me to examine. His calluses have calluses. "Look at them well," he urges. "You don't get hands like that without tasting hardship."

Where the workshop stood there is now a wide stretch of road gridlocked with cars. Chen Maa squats in the gutter and rubs his eyes with his thumbs. "I come here from time to time," he says softly. "I don't know why, but it makes me feel warm inside - warm with memories. I'm a dinosaur. No one wants bicycles any more. Why would they, when they can have cars?"

It's not only Chen Maa who has tasted change. Everyone living in Beijing has experienced it, and does so on a daily basis. The city is sloughing its old skin like a giant dragon that's been asleep for centuries.

And the result is a total reconfiguration of the system. In this brave new world there's one clear goal: opulence and luxury on a monumental scale, albeit the preserve of those with cold, hard cash.

Most of the foreigners you meet in Beijing point to the forest of cranes on the skyline and shake their heads in despair. A banker friend who's been living in the capital for years takes me to his 38th-floor office window and does just that. "The city officials ought to be taken to The Hague for crimes against humanity," he says bitterly. "One day they'll wake up and realise that they've destroyed a treasure."

But surely it's all in the name of progress? My friend's face turns scarlet with wrath and his hands begin to tremble. "Another couple of years and all the history will be gone! If you don't believe me, go and have a look at the hutongs for yourself."

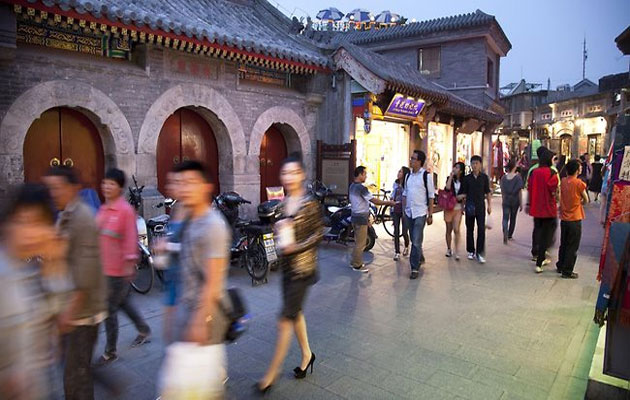

A little later I find myself in the sidecar of a World War II BMW. Well, this being Beijing, it is a Chinese copy of a Russian copy of the German original. Crouched over the handlebars is a young Frenchman named Gael. Slaloming visitors through the maze of old hutongs is how he makes a living. Zigzagging past washing lines and bent old men, hookers and their pimps, and little children with angelic faces, we seem to cleave our way back in time.

By the end of the journey I have what I think are answers. Staggering out of the sidecar, I get a flash of central London - where the Georgian regency reshaped vast swaths of a city whose classical architecture is held so dear. The same went for Paris under Haussmann - grand, sweeping boulevards that are at the heart of Gallic national pride, created at a forgotten cost.

By good fortune I am staying at the Opposite House, a new colossus of a building in the Chaoyang District. If it were anywhere else, the people who worked there would be gloating. But modern China is awash with architectural marvels, which shouldn't be any surprise. After all, the dragon that sloughs its skin today is the very same one that brought us the Great Wall yesterday.

My banker friend phones late in the afternoon. He steers the conversation on to the glory of hutongs, all cramped and forlorn. Then he asks about the hotel. I scan my enormous room - sleek lines, calm serenity, all of it peppered with amusing quirks of contemporary design, not to mention enough space to swing a tiger by the tail. "It's horrid," I lie. The banker expresses approval and says he'll be right over for drinks.

After a good many single malts in Punk, the basement bar, he leads me outside to inspect Sanlitun Village, the pristine plaza of luxury shops that has sprouted up adjacent to the hotel.

On the only other occasion I have visited Beijing, I spent most of my time lost in the labyrinth of the infamous Silk Market, buying pirated DVDs of just about every movie ever made. So my memory of Chinese shopping is one based not only on discount fakes, but one in which space simply didn't exist.

Sanlitun Village wallows in the kind of neat, designed landscape that's such a novelty to the nouveau riche of modern Beijing. There's every imaginable brand name in the line-up, but the labels aren't as much of a thrill to the visitors as the pure sense of expanse, which only those who've made it can afford to populate.

The next day I read an item in the local English-language newspaper about how the latest zillionaire in town has made it big by renting out wrecking balls. But even he, the article confesses, fears the day when there is nothing left to wreck.

Just as I finish reading the piece, a student of English approaches me, hoping for conversation. I ask if he is bothered that all the old buildings are being torn down. The student stares at me blankly, then blinks.

"We don't need history in a material way like you do," he says, "because we hold our history in our hearts."

Not long after that conversation, I fly to Hong Kong. I am still thinking about change and Chinese culture, and about space as well. On the surface, the former British colony is so very different from the mainland, but it makes for a fascinating lens through which to peer into the future of China.

Roam around Hong Kong and you can't help but be struck by the sense of self-confidence, mixed with a long-established grounding in personal wealth. I've never seen so much bling or so many skyscrapers jammed into such a confined space. But at the same time I am deeply impressed at how Hong Kong has held firmly on to its hybrid culture. As with mainland China, the broad strokes may change, but the details stay the same.

At the Wet Market, I get chatting to a woman who is prising shells off live turtles. She says there is no meat like fresh meat, and that even though the market isn't as ramshackle as it once was its soul has remained unchanged. I ask if she is fearful of change. She grins a big, toothy grin and rips the shell off another turtle with her hands.

"If you can't keep up, you'll get sucked under," she says. "What's the good of selling turtles if no one wants them any more? If they don't want these, I'll sell catfish, and if they don't want that, I'll sell eels instead."

I think back to Chen Maa, King of the Spokes, and how he has been left behind. He hasn't kept up in a city where all the old alleys are being replaced by broad avenues, a place where bicycles are things of the past.

The woman picks up a live shell-less turtle and chops it neatly down the middle with a cleaver. "Change is good," she says, bringing the cleaver down again. "Without it we would be standing still."

by : Priti Prakash

The year 2025 dawned with New Delhi gazing lovingly into the mirror of its own expectations. After a...