New delhi:

New delhi: Had Nirbhaya's juvenile rapist and killer been born a few months earlier, he would have been waiting for the noose to tighten around his neck, like his co-convicts.

But, now he may walk out after just three years in a reformatory, with a sewing machine as a farewell gift.

Watching him walk out free just because of an ill-timed evolutionary mishap would make many of us feel like Bhishma witnessing the disrobing of Draupadi.

Like Bhishma, who was bound to Hastinapur and its laws, we too can just wring our hands in frustration because extant laws forbid strict punishment for even the most heinous crimes committed by children below 18.

So, the 17-year-old drifter who first got drunk with his friends on a moving bus, then lured Nirbhaya and her friend into the vehicle in his sing-song voice, raped her with his five accomplices, inserted a rusted L-shaped tool to eviscerate her and then threw out the unconscious, bleeding girl to die on the road would be free to board a bus that could take him anywhere--both literally and figuratively.

And, like Bhishma and other darbaris, we would all be watching with our hands tied to the back, heads hanging in shame.

If events unfold according to schedule, the boy-who-can't-be-named, could walk out any time. Perhaps, he would be one of the onlookers when people gather for a candlelight march in Nirbhaya's memory on the fourth annual reminder of the ghastly incident, smirking, smiling or crying--depending on his mindset--at the memory of that night.

We do not know his name, do not recognise his face; nobody knows if he has been suitably reformed--Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi argues he should be released but believes he was not given any reformative therapy. Those keen to show him in a better light say he is an "award-winning" painter who loves to draw women in various attires and moods and cook when he is in the mood.

But, we also know that he never confessed to his crime, obviating thus, any need for regret and repentance. And since nobody would be watching him--it would be illegal, isn't it?--we would be at the mercy of his conscience. Hopefully, he found one in the reformatory.

There is, of course, the possibility that we would all be proved wrong and the boy who raped and killed would go on to become a responsible, reliable adult, ready to be invited home, picked as a groom by somebody courageous enough to ignore his past. Those who watched him in the reformatory believe he fears god, that he fasts during a religious festival. May be now he fears the law too.

It is true that laws can't be changed for individuals. Just because Nirbhaya's rapist is getting away with mild punishment, the criminal justice system can't be subjected to reactionary, post-facto overhaul. God forbid, if tomorrow a 14-year-old commits a similar crime, we wouldn't be shouting silly for turning Tihar into a crèche.

Yet, as Maneka Gandhi rightly said, when the juvenile walks out free, it would imply we failed to ensure justice for Nirbhaya. "Let us not confuse justice with the law. The law said that he could only go to children home... That's the anomaly we are trying to correct. So he served his sentence and according to the law he is coming out. And there is nothing we can do about it until or unless he commits another crime. So that is all we can do," Gandhi argued recently.

Could this hand-wringing have been avoided? While convicting Afzal Guru to death for his role in the attack on Parliament, the Supreme Court had made an interesting observation: "The incident, which resulted in heavy casualties had shaken the entire nation, and the collective conscience of society will only be satisfied if capital punishment is awarded to the offender."

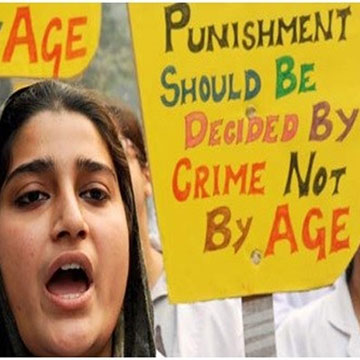

So, let us ask ourselves, a simple question: Did the punishment to the juvenile guilty of Nirbhaya's rape and murder satisfy the collective conscience of the nation? Did it deter other juveniles from committing the same crime or the mild reprimand act as an inspiration and an excuse?

Just a year later, when five persons were accused of raping a photo journalist inside Mumbai's Shakti Mills compound, one of them immediately drew attention to his juvenile status to seek leniency. Perhaps he was emboldened, not deterred, by the fate of Nirbhaya's juvenile murderer.

When we talk of justice, an old aphorism always comes to mind: Justice should not only be done but it should also be seen to be done. Often we argue that the law should not be implemented just in word, but in its spirit. And that rules are meant to protect social functions, uphold moral values and deter criminals by instilling in them fear of deserved retribution.

Much of this wisdom, however, would sound like a cruel joke when the juvenile walks out of the reformatory to begin his life afresh.

New delhi: Had Nirbhaya's juvenile rapist and killer been born a few months earlier, he would have been waiting for the noose to tighten around his neck, like his co-convicts.

New delhi: Had Nirbhaya's juvenile rapist and killer been born a few months earlier, he would have been waiting for the noose to tighten around his neck, like his co-convicts.